In mental health settings doors or door hardware account for 50 per cent of suicide attempts. This startling figure highlights an issue that is being tackled by The Design in Mental Health Network (DiMHN) – a registered charity – and Building Research Establishment (BRE).

Managing risk in hospital settings is critical. A key issue for those who are sourcing products for the rooms and facilities in which patients are treated is understanding whether they are suitable for the intended purpose. Until now there has been no formal process across the NHS or private sector for reliably testing or assessing products’ suitability for use in mental health environments.

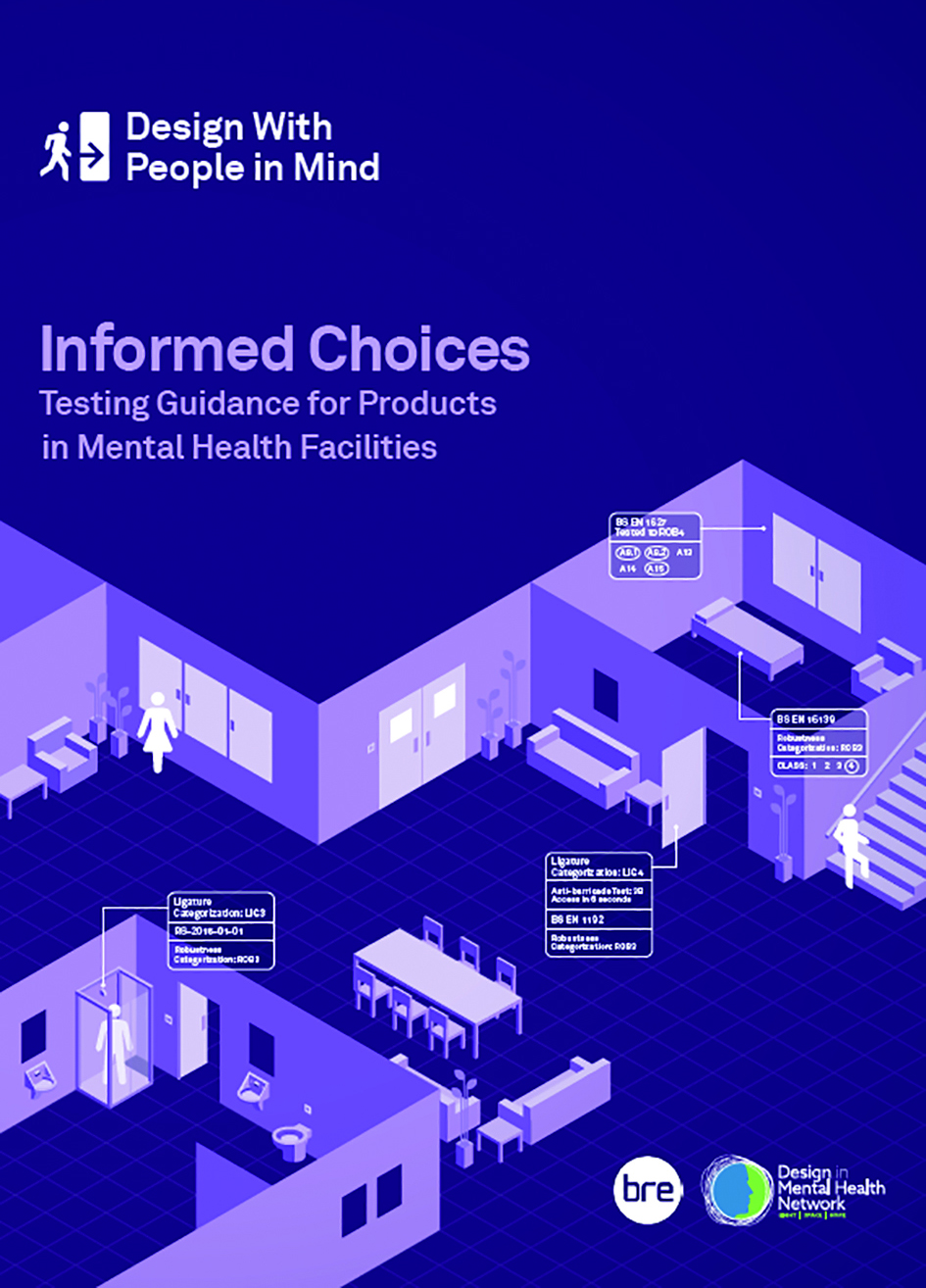

DiMHN has partnered with BRE and worked with over 100 experts during the past seven years to create a global testing method for all products used in mental health. They have also created a new document ‘Informed Choices: Testing Guidance for Products in

Mental Health Facilities’.

The Testing Guide provides testing methodologies for materials, fixtures and hardware that have been specifically designed for use within mental healthcare facilities. It brings together the many disparate requirements for these products into one document, enabling suitably qualified experts to choose the most appropriate product. It will form the basis of a new, independent declaration of performance scheme to be run by BRE Global Limited.

One of the biggest steps is providing manufacturers the ability to get an independent assessment on the ligature performance of their product by a UKAS accredited test body. This will also provide a graded performance, moving away from the absolute ‘anti-ligature’ term which is considered misleading and dangerous.

The aim of independent testing and product certification is for architects, suppliers and clients to make better product selection decisions – ultimately helping more patients recover.

In order to encourage widespread adoption by manufacturers, the demand for testing and certification needs to be high. The DiMHN and BRE have encouraged all stakeholders to pledge their support to the initiative. Like other product evaluations (e.g. fire testing for doors), the cost is covered by manufacturers as part of their development.

Due diligence

Several NHS Trusts have already signed the pledge along with leading specialist architects and main construction contractors. Signing up to the pledge for organisations means:

- Suppliers will be asked to provide DiMHN/BRE Informed Choices product performance assessment going forward. Initially this will be encouraged, with preferential consideration given for products backed by independent performance assessment. No minimum performance will be required, but performance of different products will be compared

- With time and experience of the Informed Choices product assessment information, this will become a mandatory requirement by 2025.

Philip Ross, a director at DiMHN (and CEO of Safehinge Primera) says the industry and NHS Trusts need independent testing to ensure due diligence on safety has been done and to gain clarity on where the risk exists, so everyone can move forward in terms of creating safer doorsets, products and ironmongery. “There is definitely a change of mindset post-Grenfell about the independence and verification of safety claims,” he says. “We are not quite in the same realm with mental health – people aren’t knowingly selling products that are unsafe – but manufacturers will make claims that cannot be substantiated and may not have considered the consequences of what is in effect just a marketing claim. For example, claiming a product is 100 per cent fail-safe or anti-ligature is communicating that it’s a risk-free product and that’s not

a responsible claim to make. So we want to support people with a framework; our ligature assessment is within a range from one to five. We never say it is 100 per cent fail safe.”

Cath Lake, director at architect practice P&HS and board member of DiMHN says the testing makes the process of choosing products more straightforward. “We normally have to get every product in to test and the nursing team also needs to know how to operate it. No product is tested in the same way so we have different results. We need regularity so we can advise clients of what’s there and how it performs and so they can make the informed choice. We need zero subjectivity – the only subjective is how it looks and ease of operation.”

Demand for testing

The testing process is now available to any manufacturer and Ross hopes that awareness will now increase so that more manufacturers seek evidence of their performance claims and that specifiers and clients start demanding third party independent testing evidence when presented with products. Ross says it is much like PAS24. “The testing of a door is a complete system not component nature. When you change a lock on a door it can change the overall performance of the door system;

we believe the same is true in a mental health setting.”

Richard Hardy, former managing director at BRE Global, has been instrumental in developing the testing programme. He likens the journey to when the BSI introduced Isofix for baby car seats. “It was a catalyst for change as it showed manufacturers how a product really performed rather than how they had convinced themselves it did. While it was possible to create a 100 per cent safe seat it would look like a steel cage filled with polystyrene and foam so would be utterly unuseable. The solution had to be practical, something people could use everyday and would strike a balance between risk, useability and aesthetic.

The culmination was Isofix which permanently changed how you fix a child’s seat in a car. It is the same with mental health products: you can put a mental health patient into a blank stone room to keep them safe but then they won’t get better; the aesthetics matter.

“When you have completely independent testers they’re looking at defeating something. That’s the right mindset. We can look at the door and see design tests to reveal weaknesses the manufacturer may not have found. In any certification programme or testing that’s what we’ve always done. Sometimes up to a 40% fail rate. It’s not that anyone wants to pass off unsafe products but we can get results they don’t expect.”

The BRE testing for mental health products has explored every possible way to create a ligature. Hardy explains: “Some product risks are simple that trusts and clinicians can assess but we have a whole range of results for ligature. We can create a ligature with a load going vertically for example, using a chair for a downward load. We look at what can be achieved and show the load we can generate at 3, 6, 10 and greater than 20 kgs. The aim is that the clinician can get an idea of where the risk is so they can know which environments these products can be used.

Client involvement

Jen Aspinall, design manager at Vinci Construction who has worked on many mental health settings, says there are also different scales of mental health patients to consider. “Not everyone is a suicide risk – you might have a pensioner with who has little to no grip, or someone with dementia who needs to recognise something as a handle. There are different service users groups and every trust has a different approach so there is more to consider than just ligature risk.”

The key to successful specification, says Aspinall, is to work closely with the NHS Trust. “The trust knows their day to day but they don’t know what information to give you. So you need client engagement really early on, in the pre-construction stage, so you can have tough conversations and start a discussion, get the information from the client and get product samples. You can’t assess whether you can grip or do damage with it from a drawing. From a commercial perspective bearing in mind NHS budgets are tight, this means you can develop a risk acuity plan. You might choose a door for a high-risk bedroom that scores a 4.8 for example but in the MDT meeting room, that isn’t identified as a high risk room, you could reduce that to a 3.5 scoring door on those places. And in seclusion areas that’s an even higher risk. You can start to form a baseline specification.”

The consequence of a mistake is a loss of life. That’s what this boils down to. It’s about preservation of life"

Philip Ross

Ross says the document enables the NHS Trust to have full awareness and then marry a clinical practice strategy with a risk reduction strategy. “We can help the NHS and the construction sector make more informed choices, make better decisions by better understanding the differences in performance between product a, b and c so they can choose the best product or the safest product.”

Cath Lake says it’s vital to work with specialists as often it’s smaller practices with little experience in mental health who could make mistakes. And Ross presses home that in these settings mistakes in specification are unacceptable. “It is really important, as the consequence of a mistake is a loss of life. That’s what this all boils down to. It’s about preservation of life.”

Read more about the work of the Design in Mental Health Network at dimhn.org

Find out more about the mental health product testing and download the Testing Guidance at bregroup.com/services/testing/mental-health-

product-testing/